Mentoring in the Maritime Industry

Apr 20, 2016 Murray Goldberg 0 MentorshipThe Value of Mentoring in the Maritime Industry

You may recall the importance of “informal learning” – learning that takes place outside of curriculum-based courses. By many estimates, as much as 70% of professional knowledge comes from various forms of informal learning. There are very few forms of informal learning as effective and personal as mentoring.

This article looks at mentoring in the maritime community. It discusses the impediments to mentoring, what mentoring is, and the characteristics of healthy mentoring relationships.

Impediments to Mentoring in the Maritime Industry

Mentoring relationships can take a variety of forms, but the most traditional (and a very effective) form of mentoring is face-to-face mentoring. However, despite the prevalence and effectiveness of in-person mentoring, it is applicability can be limited in the maritime industry.

The problem is that opportunities to interact face-to-face with a maritime mentor are rare due to the isolation of being at sea and the small size of most crews. Compare a maritime career to a traditional shore-based occupation such as being a teacher or accountant. These professionals may have access to hundreds of potential mentors in their office and through bodies such as professional associations which meet regularly.

When mentoring in the maritime industry does happen, it often occurs between people serving on the same vessel, and is typically short-lived because one of the participants sooner or later ends up on a different vessel or different shift. This is a problem as mentoring relationships are usually best when they are long lived and when the mentor is not in a position of influence over the protege.

This difficulty of mentoring in the maritime industry is especially unfortunate for a number of reasons:

First, maritime practices and traditions are very deep and need to be conveyed from one generation of mariner to the next. Mentoring would be an excellent way of conveying those traditions and knowledge.

Second, the maritime industry is in desperate need of attracting new, bright young mariners. One of the best ways to do that in any industry is to raise the awareness and knowledge of the industry through the availability of career mentors and role models. As it stands now, how many mariner role-models are a young person likely to run into in the course of their daily lives? Very few – since most will be at sea! Young people need to see the profession as being full of challenge and opportunity.

These factors make mentoring a particularly valuable activity in this particular industry. There is a real disconnect: a huge need and very little opportunity for mentoring. Fortunately technology has provided a mechanism for people to interact with one another regardless of location. That technology can be used to support mentoring relationships – a form of mentoring called e-mentoring. I will write more about the activity of e-mentoring in the future, but for now let’s first make the distinction between mentoring and training.

Mentoring is Not Training

In the maritime community, there is a wealth of un-codified cultural and general industry knowledge that can only be learned through informal means. Mentoring is a very powerful way to share some of that knowledge.

However, there is, or at least should be, a clear division between mentoring and training. I have seen organizations who attempt to use mentoring, sometimes in the form of job shadowing, as a way to accommodate for shortcomings in their training operations. This is a mistake. Mentoring and training are each very valuable, but they are different activities used to achieve different outcomes. Mentoring is an outstanding supplement to training, but never a replacement for excellent training.

Why is this?

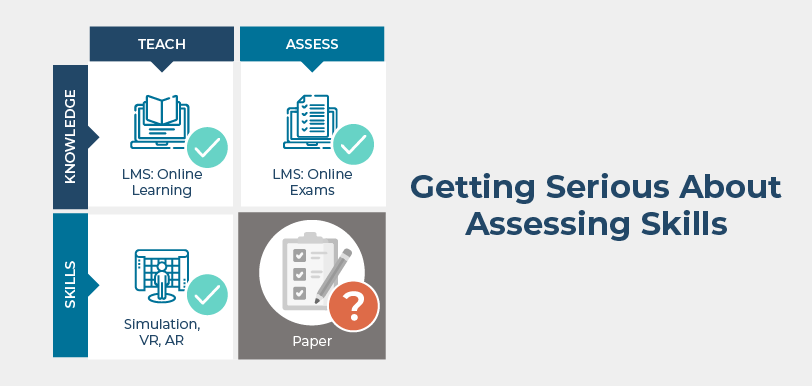

One main reason is that the process of mentoring is different than the process of training. Mentoring does not lead to reliable and valid learning and assessment. Training should be formal, structured, standardized, and well analysed. Its outcomes should be reliably and validly assessed. Mentoring is not formal, structured, standardized nor well analysed. Its outcomes are rarely assessed.

There is also a major difference in the topics covered during training and mentoring:

There are skills and knowledge a mariner or other maritime worker needs to know to do their job safely and efficiently. Those must be trained.

On the other hand, there is also personal knowledge a maritime worker needs in order to make important personal, professional and career-related decisions. This is what mentoring is for.

A mentor may not be able to tell a protege how a particular piece of equipment is used, but they can tell them what it is like to be at sea for extended periods of time, or what broad opportunities exist for advancement in their industry niche.

Training and mentoring have different goals, teach different knowledge, and require different techniques and tools. They are both extremely valuable, but are very different from one another.

Then What is Mentoring?

Mentoring relationships are confidential, trust-based, voluntary arrangements between a mentor and protege. The mentor is someone with significant experience in an area, and the protege is someone who either wishes to work in that area, or is working their way through the ranks.

The idea is that the mentor is able to provide guidance based on their experience, which will help the protege make more informed professional choices. Mentors are role models, advisers, supporters, network enablers and sources of wisdom, experience, and inspiration. The most important characteristics of a good mentor (other than expertise and experience) include a genuine desire to be helpful, good communication skills and patience.

What Makes a Good Mentoring Relationship?

Good mentoring relationships and interactions have a number of characteristics.

- Long-Lived.

The best mentoring relationships are often long-lived. With a long-lived relationship, the mentor has much more intimate knowledge of the personality, goals and context of their protege. They are able to follow the protege through many stages of their career. And it is this intimate knowledge that enables the mentor to provide appropriate guidance. - Personal.

It is important to realize that mentoring relationship are personal relationships. Mentors should be personally vested in the lives of their proteges, making them caring and responsive mentors. The personal connection creates a responsibility to the protege to respect the significance of the mentor’s guidance.

Likewise, proteges need to feel comfortable sharing their questions and concerns with their mentor – especially those which might be difficult to share with a superior or peer. They need to feel as though they can trust their mentor, and this trust only comes from respect and, for lack of a better word, intimacy. - Unconflicted.

Mentors should never be in a position of conflict or influence with respect to their protege. They should not be a superior of the protege, part of a regulatory body which oversees the work of the protege, from a competing company, and ideally should not work at the same company as the protege. I realize that this last point goes contrary to most maritime mentoring relationships. I have heard from dozens of mariners who owe huge debts of gratitude to, for example, a captain from their past who took them under their wing and acted as their mentor. These were, undeniably, very successful mentoring relationships. Therefore, you may or may not agree with this point, but it is important to consider it, regardless. Most experts on mentoring argue that such a relationship can never reach its full potential because there will be some topics which are difficult to broach due to the superior-inferior relationship and conflicts of interest. - Mutually beneficial.

The benefit of the mentoring relationship for the protege is generally well understood. But interestingly, whenever you speak with a mentor, you invariably hear of the incredible benefit that they, too, have derived as a result of the relationship. For myself, as a past mentor to a very large number of students, I found that being a mentor challenged me, and kept me connected with and informed on the needs and issues of young academics. I always learned something from each of these relationships, and every one of them was highly satisfying and rewarding – especially when I felt as though I made a real difference in someone’s life. The benefits of mentoring flow both ways – being a mentor is not a strictly philanthropic experience.

Clearly these four characteristics, while arguably some of the most important, only touch the surface of what makes a healthy mentoring relationship. I will write more on the nature of mentoring in future articles.

Follow this Blog!

Receive email notifications whenever a new maritime training article is posted. Enter your email address below:

Interested in Marine Learning Systems?

Contact us here to learn how you can upgrade your training delivery and management process to achieve superior safety and crew performance.